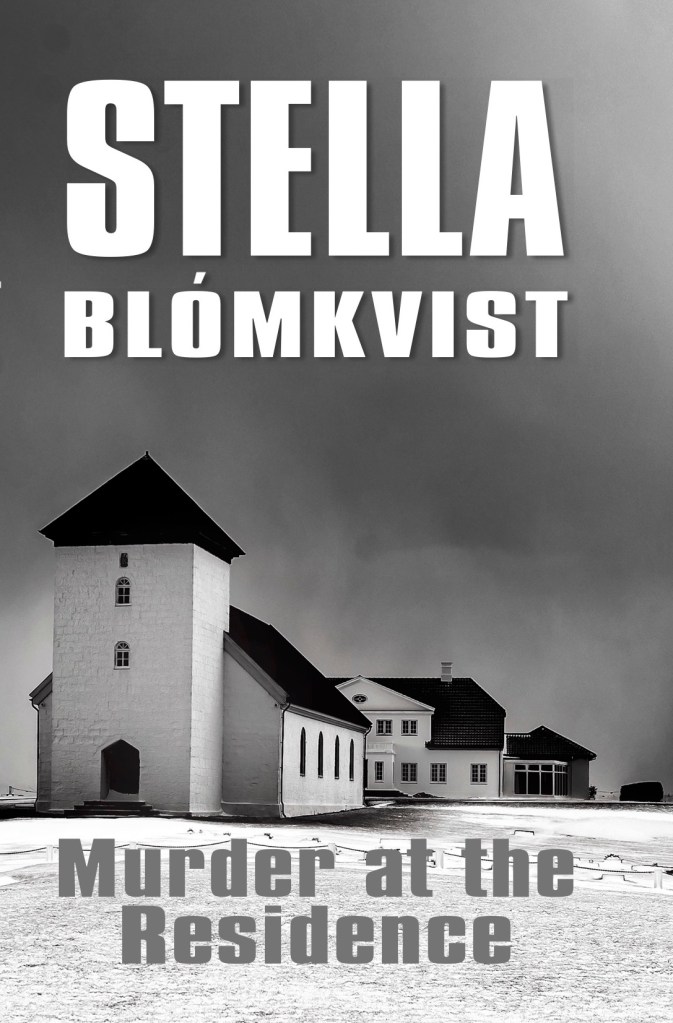

STELLA, shrieks the cover of the novel, implying that you should know who Stella is. The whole point, of course, is that no one knows who Stella is. Everyone in Iceland knows Stella Blómkvist the character, almost no one knows Stella Blómkvist the author, although according to the news release that accompanies my copy, just about everyone has been suspected of being Stella. This translation by Quentin Bates, of Murder at the Residence, is new, but the novel itself is not: published in Iceland in 2012, it’s set during the ‘pots and pans revolution’ of early 2010 when protests outside the parliament in Reykjavík brought down the Icelandic government following the financial crisis. The blend of political intrigue, seedy corruption and take-no-prisoners protagonist lead to a mix as potent as Blómkvist (the character)’s tipple of choice, Jack Daniels.

Recently, I’ve found it difficult to relate well to outlandish and fantastical fiction. I need stuff that’s quite literal. I want to spend time with characters I like, but there has to be a realism there too. Some of the incidents that Blómkvist is investigating are fairly horrific and indicate cross-border organised crime: that is no fun. But what Blómkvist (the writer) describes and Blómkvist (character) explores is what agency a private citizen might have against vested interests. Lawyer Stella gets involved with causes without blinking twice; she acts on reflex. She’s up against a police service that occasionally plays dirty but she holds her own. She cracks wise but she also uses certain stock phrases (the cops are always ‘the boys in black’ or ‘the city’s finest’, her car’s her ‘silver steed’) and ends many chapters with a throwaway aphorism ‘as mother said’. I’m sure translator Quentin Bates will have raised an eyebrow more than once, but I’m equally sure that he will have loved much of what he has been given to work with. Blómkvist loves her daughter and is happy to act on a sudden passion but for all that she acts on behalf of the powerless, she’s cynical and lacks the kind of idealistic doctrine that many counterpart detectives might have. It’s almost as if, each time she acts out of compassion, her main motivational driver is to stick two fingers up at either a holder of power or someone who has just generally annoyed her. She reminds me of other characters I’ve liked in novels by Simone Buchholz, Gunnar Staalesen and, most recently, Lilja Sigarðardóttir.

We can’t ignore the historical backdrop to all this. It’s easy to find pictures on Wikpedia of the very incident during the pots and pans revolution in which a character is tear gassed and has her shoulder dislocated. Occasionally it’s easy to forget, as we sit in comfortable surroundings, that there are moments of drama, and we may take part in them (and do what, exactly? That is the interesting challenge) but sometimes we are in the periphery and we are just getting on and doing what we are doing. Murder at the Residence was written fairly soon after the revolution: too soon to be able to draw conclusions. So we have a vantage point that the book’s original readers would not have had. It’s an added feature of this enjoyable and rewarding novel that we get to read what’s on the page, and wonder what was on the minds of its 2012 readership.

Thanks to Corylus Books for the review copy and to Ewa Sherman for the blog tour invitation.