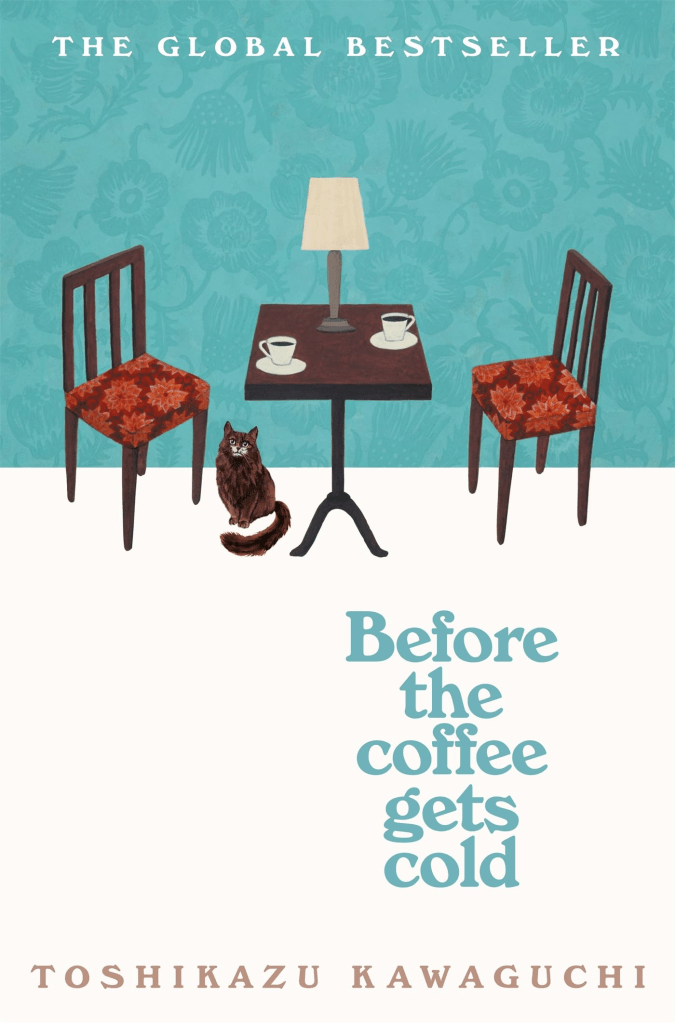

Of all the Japanese novels that have stormed the UK over the past few years, Before the Coffee gets Cold has perhaps had the most traction. It’s everywhere. It has taken me a while to catch up, and now there is a whole cold coffee series. Yet there’s been quite a mixture of views from the blogging and reviewing community. I keep reading that Toshikazu Kawaguchi is a playwright who can’t write prose. Every reader has cried, except the ones who haven’t. And there is some criticism of apparently cliched and stereotypical ideas about the role of women.

The premise is that there is an underground coffee shop in Tokyo called Funiculi Funicula. If you follow certain convoluted rules you can travel back in time to relive a moment of your past, as long as it took place in the coffee shop. An important rule is that you will not be able to change the present. The rules mean that there aren’t that many people who choose to make the journey and each of the Coffee books covers four mini-stories. Each story deals with a kind of relationship: in the first book we meet four women seeking reconciliation (or not) with a boyfriend moving away for work, with a husband who has dementia, with a sister, with a daughter. Within those relationships, it’s fair to say that the women are not the more powerful partner. I can certainly see why the suggested courses of action that follow the time-travelling have upset some readers, while others have found the undoubted emotional pull compelling.

At least two of the characters react to their time travel in ways I disagree with. Now it’s a sad fact that people do things all the time that I disagree with, so the next thing is to try to work out why, and what the author wants us to do about it. The most obvious observation is that all four characters want to go to the past because they want to understand, or to see things differently, or to be reconciled. In short, there is already a power deficit. It’s disappointing that that deficit seemingly can’t be overturned. What can happen, instead, is greater understanding and a different perspective. It is this that has found resonance with some readers, leading as it does to a message of potential hope and an attitude that by trying to understand other people’s points of view, we can act in a more measured way, living ‘better’ and perhaps avoiding future missed opportunities.

I don’t know whether I’ll continue with the series, but I’d hope for a couple of things: first, that there might be more male characters. Currently, they are all secondary characters and although that is not necessarily a problem, it would be helpful to be able to ascertain whether what’s been identified as a traditional view of gender roles holds up as such. Also: I’d love for the book(s) to be more than the sum of their parts. What I mean by that is that each story stands largely alone and there are few fully-rounded characters. In turn, these characters’ ideas of what love and duty demand them to do aren’t fleshed out and examined. It’d be a shame if the whimsy of the format got in the way of an exploration of what love, duty and reconciliation might really involve.

Thanks to Picador for the review copy.

Although I agree that there is a power deficit before the women ‘travel’, they have the power to change their future.

Fair point!