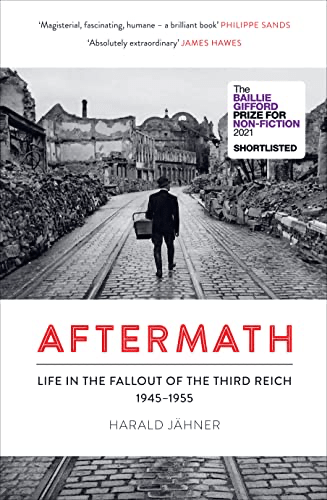

Today is the 80th anniversary of VE Day. Up the road from here, there’s bunting and cake and celebration, and quite right too. For us in most of the British Isles, that’s that. Except in the Channel Islands, there was little acknowledged collective need for any kind of soul-searching. We can go straight from tales of bravery to the modernisation of the Attlee government. Other than the Marshall Plan and the Berlin Airlift, and perhaps the split between west and east, we don’t talk much about the defeated. Besides, certainly before the AfD entered the Bundestag, the Germans have had a reputation as a people who have reckoned with their past. But what really happened eighty years ago? Harald Jähner tried to find out, and discovered a reality that was less clear-cut.

I’m not sure that we should be so surprised. We would expect physical, mental, emotional and financial chaos, but experienced highly unevenly. A nation that had lived under a government of blind certainty for 12 years would take a while to accept and learn new truths. And as Jähner points out in his forward, ‘the most important changes were played out in everyday life, in the organisation of food…in looting, money-changing, shopping, and also in love’.

Jähner takes a thematic approach, dealing in turn with the idea of ‘Zero Hour’, the ruined cities with mountains of rubble (some of which was still being cleared in 1976), the ‘great migration’ of displaced people, the return of pleasure and of culture, the black market and petty thievery – and the currency reform that put paid to much of it, the role of the Cold War superpowers in re-education and the extent to which abstract art benefited from being part of the geopolitical front line and, finally, the way in which the Germans of the late 1940s categorically did not reckon with what had just happened. There is no doubt that Jähner is disappointed by that generation’s inability to rise to the occasion. He is appalled when ordinary Germans gloss over the Holocaust, or think of themselves as victims of the Nazis, and he is disgusted by the pogrom in Kielce that showed that antisemitism did not end on VE Day. He is frustrated when local Nazi leaders pop up again in managerial positions having been originally purged. He is saddened when reform-minded journalists are subject to small-p politics. He wants the refugees to be treated better. He wants this generation of Germans to have behaved better.

Of course, it would be hard to read this book if its writer did not take these positions. Jähner tells us stories of ‘displaced persons’ – Jews, Poles and Russians all with differing notions of what ‘home’ might be like, and Germans forced west by the new Polish border. None received a warm welcome elsewhere in Germany: they found it hard to plant new roots or were simply rejected. That’s hard for us to understand, but we know reactions like this to displaced people are quite mainstream even today. And Jähner points out that ‘five years after the war, West Germany had almost 10 per cent more inhabitants than it had before the fighting broke out, yet a quarter of the country’s housing had been destroyed’. We learn that the identity of the Volk is prefaced by a local or regional tribalism. But eventual integration was bolstered by radio and television that flattened dialects and encouraged the spread of standard German. And a paradox emerged that expellees from the eastern territories were more likely to harbour nationalist views longer than those they came to live amongst.

The sheer scale of Jähner’s sources and his love of telling stories (especially about those close to journalism and publishing) mean that it’s difficult to take too wide a lens. What we seem to discover is a people who are just trying to survive. They themselves can’t see the big picture. Ordinary folk were appalled by the rise in petty criminality after the war, and Jähner isn’t having it: ‘A collective perception could hardly be more distorted…it was only after the war that the Germans saw themselves becoming perpetrators – because they were stealing coal and potatoes. The fact that in Germany alone half a million Jewish fellow-citizens had been stripped of their possessions and driven from their homes, and in the end 165,000 German Jews had been murdered, was never so much as mentioned…double standards were not in short supply.’

It’s easy to be outraged, and Jähner encourages it. But he gives us more and describes the ways in which a new public discourse took its first steps, even if test screenings showed the Americans that the Germans were not yet ready to watch Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator and laugh at Adolf Hitler. It would take years – and in the meantime ‘Germans kept their heads down, they grew tongue-tied, they chattered away unmoved, manically, as if they had been wound up.’

It would take another generation for a real reckoning. But to come to this book and have that as your main takeaway would be to miss the point somewhat. Jähner shows us those several levels of chaos through which a people simultaneously defeated and freed are muddling through. To have them confront a terrible truth at the same time might have been too much to ask even if Jähner is quite entitled to ask it. Instead, our takeaways should be that of a full-colour rendition of a world we too often see only in monochrome. There’s some tough material in here, but it’s essential reading.

Thanks to Random House for the review copy.

Cafethinking has featured many of the Imperial War Museum’s series of reissued WWII novels.