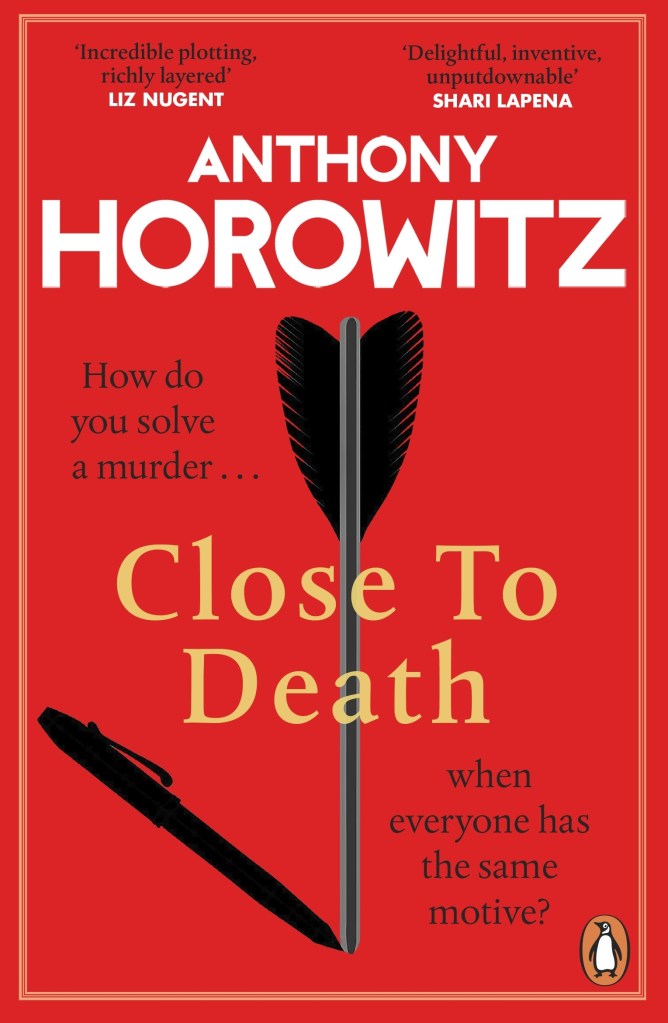

What has the crime genre done to Anthony Horowitz, that he should subvert it so? The Susan Ryeland/Atticus Pünd series has been an enormous hit both on the page and the small screen, and the Hawthorne series reaches its fifth instalment in Close to Death. All these critique a kind of cosy crime that has been a particularly successful part of the genre, not least for Horowitz himself. The sort of subversion that these books specialise in can be created only by a writer supremely confident in their understanding of what makes the genre tick, but now even the Hawthorne series sees an impatient Horowitz branch off in new directions. The first four titles have seen an ex-police private detective, Hawthorne, and his sidekick ‘Anthony Horowitz’ tackle mysteries. This time, Horowitz is on his own, telling a story as described in Hawthorne’s contemporary records.

The premise once again sees Horowitz under pressure from Hilda Starke, his bossy literary agent, pushing him to meet deadlines and apply himself. (Since Horowitz appears to be one of the hardest working crime authors, this is clearly meant to amuse us, and shows us that very little of ‘Horowitz’ is meant to depict Horowitz accurately.) Anyway, we read about one of Hawthorne’s old cases, one in which a neighbour from hell arrives in a tight-knit housing development and is dispatched directly to hell (probably) by one of the others. It’s a kind of locked door mystery in that there’s a closed cast, but just to make sure, Horowitz gives us a critique of the traditional locked door story as written by the likes of Edgar Allen Poe.

This time, Horowitz and Hawthorne don’t work together – they hadn’t met when the murder was first investigated. Hawthorne has a different sidekick and the relationship between the two provides the real energy for the novel. The murder itself is an interesting puzzle, sure, but the victim is so odious that we’re not necessarily that bothered about who dispensed the justice. What is more interesting is the relationship that the characters have with the whole story now that Horowitz is investigating it afresh. There are loads of red herrings but a clue that even I could not fail to spot. The story contains plenty of the slight asides and references that delight Horowitz’s fanbase.

The ending is deliciously yet frustratingly ambiguous. To use the current vernacular, does Horowitz believe that he has ‘completed’ Hawthorne? Or just that his agent will be off his back? We hope for instalment six, and for Horowitz to shake it all up once again.

Thanks to Century for the review copy.