Days at the Morisaki Bookshop sounds as though it is going to be a dreamy, hazy tale. This short novel, translated by Eric Ozawa from the original Japanese tale by Satoshi Yagisawa, promises to be about books and bookshops. Like any good bookshop, though, the Morisaki store is the door to a world of discovery, and this novella explores how books can open your eyes but what you see is fundamentally up to you. The blurb on the back says it’s a ‘tale of families, love, new beginnings and the comfort that can be found in books’ but personally I think it’s about courage.

Takako, the lead character, is 25 going on 17. She splits up from her boyfriend when he tells her he’s getting married to someone else. She quits her job and goes to live above her uncle’s bookshop, helping out in the store. Yagisawa goes out of his way to make Takako unsympathetic. Almost anyone who picks up this book will be a bibliophile; Takako doesn’t read. She’s self-absorbed and somewhat snippy. Uncle Satoru, on the other hand, is a star. He tells his niece that the bookshop will be her harbour – ‘it’s important to stand still somethings. Think of [this] as a little rest in the long journey of your life.’ He talks of the importance in having the courage to do what you want in life.

And things duly pick up. By page 34, Takako has finally picked up a book and you know what, she gets reading. More to the point, she picks up that second hand books have a history that can’t be provided by brand new copies. When you see a page corner folded down, or a comment in the margin, you’re linked to others who have travelled that journey before you. Thing is, as we discover, Takako isn’t a dead loss after all. Now she reads books, but it turns out she could always read people, as she does with Takano as he pursues Tomo, and as she later manages with Momoko, Satoru’s disengaged wife.

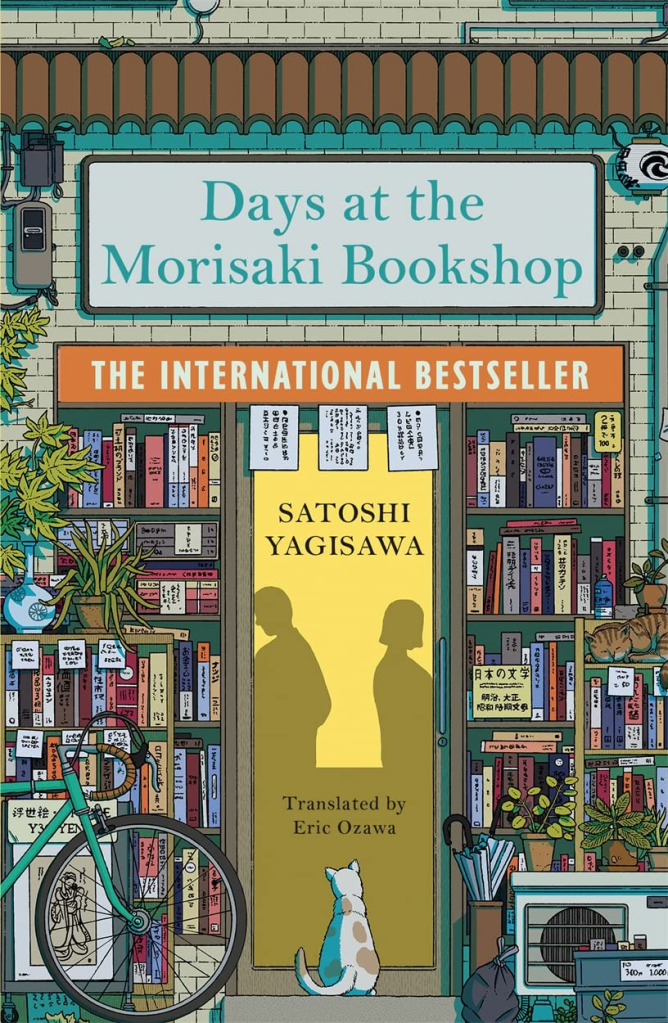

I’d like to feel that the Morisaki Bookshop, with its cast of regular customers and ramshackle appeal, reflects the vibe of Jimbocho, Tokyo’s book quarter. Compare the front cover with scenes from Jimbocho. But I am not sure that Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is that accurate a title. Most of the action takes place elsewhere and Takako moves out on page 67. The last quarter of the novel involves a trip to the mountains. Perhaps these are Satoru’s days at the bookshop. But Takako claims them for her own. This may seem like an arcane point, for without part 1 of the book, part 2 can’t follow. But it makes me think about the descriptors we put on different times of our life. For Takako, this is the story of a renewal. She relates to Momoko as an adult. She pursues a bookworm who was previously dumped for being boring. And she comes to terms with her split with her rancid ex, Hideaki. The scene in which she takes Satoru to Hideaki’s home so as to confront him is an odd set piece but entirely consistent with this novella’s theme of seizing courage. Later, Momoko and Satoru will need to find new courage all over again.

The book ends abruptly, and for a 170-page novel to devote its last 22 pages to acknowledgements and an excerpt for another novel from a different writer is not really on. But that’s the publisher’s fault, not the writer’s. Yagisawa has delivered something warm and uplifting, and Ozawa has brought some light and idiomatic prose. We get the feeling the tale isn’t over yet, and we wish for stout hearts and warm comfort for Takako, Momoko and especially Uncle Satoru.

Well, the story wasn’t over, because there’s a sequel. I enjoyed them both, even if they were a bit… choppy.