Having enjoyed his previous book Night Trains, and having been so ridiculously proud of being an owner of a Carte d’Orange that I carried it around, in London, until it fell apart, I had to read Andrew Martin’s newish book on the Paris Metro. By the end of it, I’ve learned a lot (including, embarrassingly, but it’s obvious when you think of it, that it was the Carte Orange), enjoyed myself and want to go to Paris again. Martin’s mission accomplished, I guess.

Can interest in pneumatic tyres and terminal loops be universal? Probably not. A great deal of the appeal of the book comes from Martin’s asides which lean in heavily to an assumed shared language with the reader. There’s a witty throwaway aside that refers to cliches used by British estate agents, and Martin is delighted that it was London’s underground, not Paris’s, whose trains ended up the shape of baguettes. An understanding of the British capital’s network certainly helps – though even if you consider yourself knowledgeable about the tube you may learn something new: in my case, that Baker Street has the only complete stone elliptical platform ceiling. Even Yerkes gets a mention, though only in passing comparison to the great (and greatly-named) Fulgence Bienvenüe, the ‘father of the Metro’.

Although he’s written about railways for years, Martin is keen to distinguish himself from railway enthusiasts, the kind that ride the Kennington Loop (at the end of the London Northern Line’s Charing Cross branch, and officially closed to passengers) and would dine out on their adventures. These people don’t dine out, he announces haughtily: my innocent interest is your outrageous obsession. Maybe he has scars from dealing with the extreme gricers.

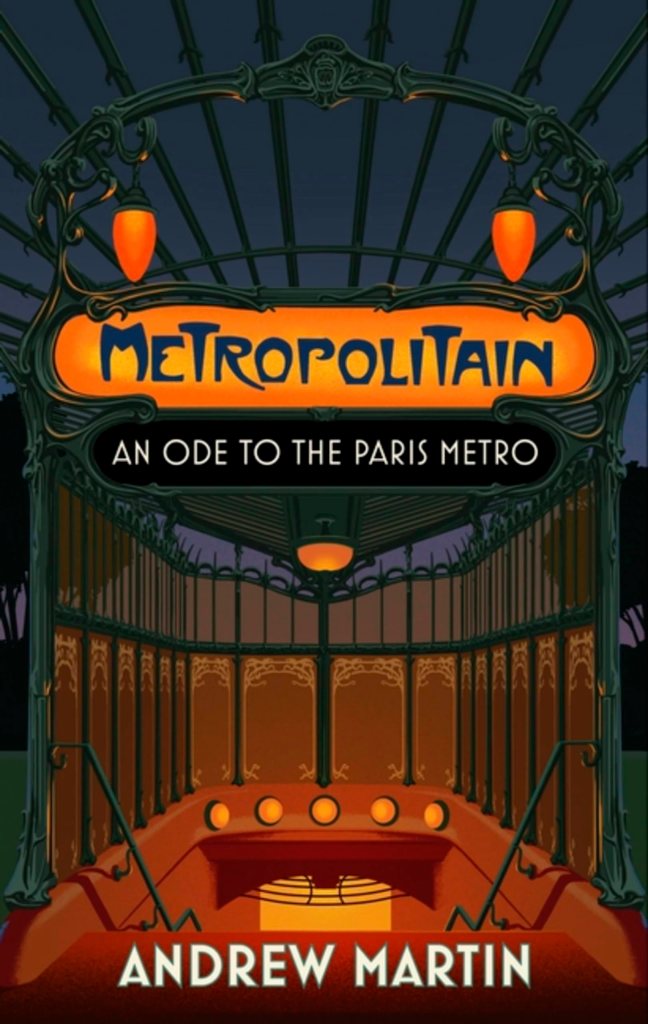

It’s true, of course, that this book is particularly arresting when it explores the mix, to be found in all transport systems, of the familiar and the other. We learn that Budapest’s closed ticket windows are masked by purple velvet curtains, and that there are no-longer-working wayfinding machines dotted around the Metro (as there are on the Underground): once-experimental and now outdated gadgetry. I finally understand why the ‘Sprague’ trains are much-loved, but the exotic station entrances designed by Guimard still leave me cold – although once I realise that the front cover of the book gives me one to look at I’m far more interested. (Illustrations, photographs or even maps are an annoying omission from this book if you don’t have other sources to hand.)

It’s also true that Metropolitain isn’t solely an ode to the Metro, but to Paris for which the underground is a symbol as rich as the Seine or the Eiffel Tower. More accurately, it’s to an idea of Paris imbibed by an outsider who’s very aware of being un étranger. You probably need to think about whether that will speak to you before starting your journey with the affable Mr Martin.

But for this reader, there was much pleasure to be had. We read about M. Omnes and his shop, Omnes Omnibus. We learn a great deal about Haussmann, and the poor relationship between city and state. The French government wanted railways that could be used to quell civil disturbances, the city wanted a service that would help Parisians get about. Paris thought it could keep out the national railways by using a different track gauge, but France insisted it be standard. So the city made its tunnels smaller instead and kept the national trains out that way. It’s good to know that debilitating turf wars are not a new thing.

Ideal (if you’re the target reader) for a winter’s afternoon, especially if you’re able to look up illustrations. Bon voyage mon petit voyageur.

Does “Petals on a wet, black bough.” feature at all?

I’m sorry Ellie but I don’t understand the reference