Spare a thought for the thousands of party volunteers who will spend the next 11 days door-knocking and canvassing. It isn’t pleasant to be on the losing side. Steve Rayson’s Badgeland is about being on the losing side. He tells us about supporting Tony Benn in the 1983 election, and, following the 1987 landslide, wonders whether all those hours spent supporting the cause have converted even a single voter to it. This memoir of of being a young socialist in Thatcher’s Britain addresses idealism, cynicism, social mobility and what it means to be part of a movement. It sounds dry; it’s anything but.

Badgeland is about being young, and about finding somewhere you belong. In Steve’s case, idealism and circumstance lead him to the Militant Tendency, a Trotskyite organisation that infiltrated the Labour Party in the 1970s and 1980s. Rayson describes what it’s like to grow up in a working-class household in Swindon, and to be the first of his family to go to university and then on to London. His father finds his radicalism embarrassing and his mother is worried that he finds digs in ‘dangerous’ Brixton, but they aren’t the only ones who don’t want to hear that the liberation of the working class lies through Marxism. Much to the confusion of idealist young Steve, the working class men down the club are more interested in buying discounted council houses and shares than in establishing a dictatorship of the proletariat. Eventually he will conclude that Thatcher has won, and that he has to find a different way in which to change the world.

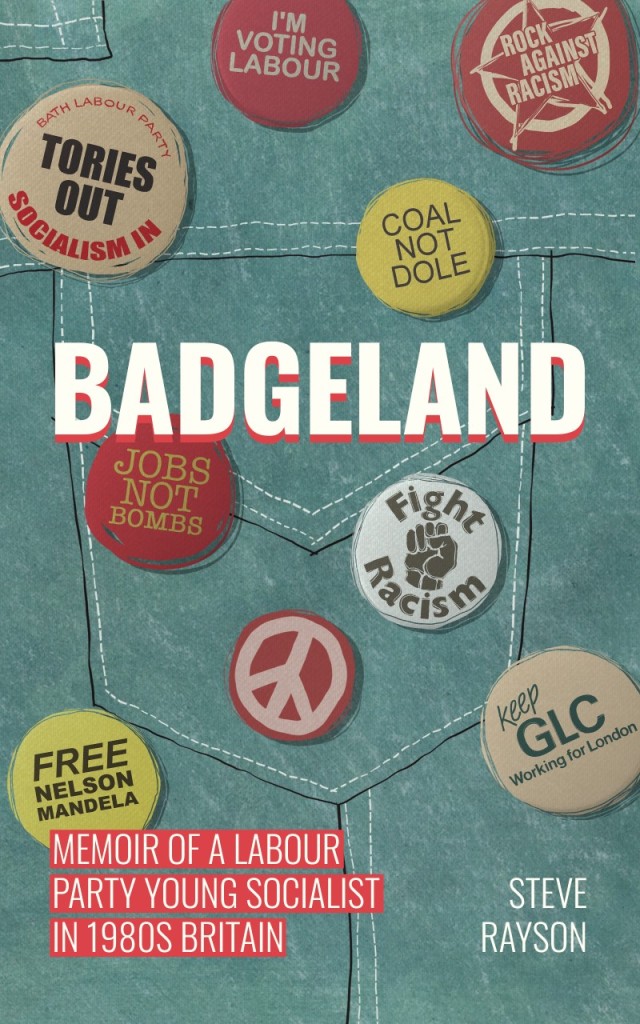

What makes Badgeland so appealing is that Rayson is a terrific narrator, and some of the book is very funny. His style is extremely self-deprecating, but without punching down on his 20 year old self. He’s affectionate towards Young Steve and particularly towards his family, friends and comrades. We get the idea that if the greatest tragedy of the 1980s was ascendant Thatcherism, Steve’s thoughtless dumping of girlfriend Alison is not far behind. He has enough grace and class to acknowledge that the greatest goal scored by Swindon Town hero Don Rogers was his goal for Palace against Stoke in 1973. He tells stories of being clumsy, awkward and gauche (and buying too many political badges), but we root for him to conquer his new surroundings, and he generally does, outside the politics.

Rayson is clearly driven, hard-working and ambitious. The first two of these attributes come from the values installed in him from his working-class family, but it is only the social mobility provided by his post-16 education that makes him able to act on his ambitions. Rayson’s parents don’t ever discuss their own ambitions so we aren’t able to see whether they were thwarted or were content. Rayson indicates that his father’s experiences of poverty as a child set Rayson senior’s attitudes to how to provide for his own family. The post-war settlement meant that Rayson junior could come out of university, shine in a public sector graduate role and set himself up for success in circumstances that favoured talented entrepreneurs. Since then, while more of Britain’s young people are now able to go to university, other opportunities (for example, to buy property) have withered. On the other hand, the shocking tales of institutionalised racism and misogyny in the 1980s remind us just how far we’ve come and how far we have still to go.

Coincidentally, Rayson and his father lose their jobs at the same time: the Swindon railway works closes just at the same time as the Greater London Council, both as a result of policies set by Thatcher’s government. Eventually, the constant defeats for the radical left mean that Rayson has to forge a different future.

Many people who were driven, hard-working and ambitious started the 1980s in various Trotskyite or communist groups to end up as hardcore libertarians and contrarians. That is a route that was probably open to Rayson, but he seems to have rejected it. He understands the role that the Trots played in his education and development. I like that self-awareness. I do wonder what direction he might have taken had he found a different friendship group in sixth form.

Badgeland asks us questions about class identity and different values held by the working and middle classes. While it’s a tale about coming of age and finding your own feet, there is plenty of discussion of the major issues confronting the UK during Thatcher’s first two terms. Indeed, as well as quoting Kazuo Ishiguro (to kind of let himself off the hook by acknowledging he may be an unreliable narrator), Rayson seems to pay homage to one of the best contemporary ‘Condition of England’ novels, David Lodge’s Nice Work. As Lodge does in one of his final paragraphs, which sees Robyn Penrose watch students by Rummidge University’s lake, Rayson closes his book wandering through St James’s Park, watching ‘groups of young people…relaxing in the dappled shade of the trees.’ Both Robyn and Rayson take hope from this scene. Rayson might not believe that things can only get better, but his time fighting and losing to the Iron Lady gave him the steel to try.

Thanks to Steve Rayson for the review copy.