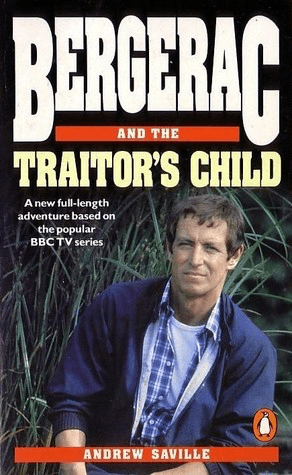

Reading Bergerac and the Traitor’s Child by Andrew Saville is like watching an all-new feature length episode of the 1980s Jersey-based cop TV drama. After BBC Books and Granada produced two volumes of adaptations of TV episodes, commissioners at Penguin decided to go in a different direction. The result is a thoroughly enjoyable novel that adds to our understanding of the Bergerac characters while remaining entirely faithful to the ‘bergerverse’.

The premise relates to the 1940s Nazi occupation of Jersey. As the war comes to a close, a French apparatchik tries to secure his future in case the expected victors of the war seek to settle scores. He tries to secure an obscure and highly valuable van Gogh painting owned by a venerable Jewish Jérriais. By the 1980s, the location of this painting is still unknown, and there are three very different people on the hunt for it: two blackmailers and a Nazi-hunter.

A major plot point is the involvement of DCI Barney Crozier and his family. We meet Barney’s dad, and his and Alice’s children Richard and Clare. It is Barney that the blackmailers have in their sights and thanks to Richard being a stroppy teenager they get more access than they otherwise might. Barney goes through some dark nights of the soul (aka getting trashed at Diamanté Lil’s) and we get to see a very different, but quite convincing, side to the character. Speaking of which, we learn about Alice’s career and that she has ‘political ambitions’ whatever they might be. Terry and Peggy have some good lines, too. And it’s good to have Francine and Michael (S3 E1) mentioned too.

Poor communication, from both the best and the worst of reasons, between the different generations of Clan Crozier means that the nature of the crime takes some time to be determined. Indeed, at first we’re not sure whether there’s been a crime at all. The involvement of a parapsychologist who is all too determined to ascribe a break-in to supernatural activity doesn’t help. And it isn’t clear that the different strands of activity do in fact fit together.

The appeal of Bergerac is based on its blend of the faintly exotic and the familiar, and Saville deploys this formula with precision. The potential for Nazi-era secrets being uncovered occurs in the TV series, and some of the characters remind us of Honeybee/Honeyman and Mary Lou Costain. Jim is able to piece things together by running around, following hunches, and relying on timely information provided by people who have learned to trust him. He works well with Terry, Peggy and Goddard even if he is happier – as the Chief acknowledges – off on his own. The one slightly dodgy note here is the final clue, provided as it is by a character whose actions are not especially plausible (though there’s an episode in which Susan Young kind of acts this way) – even if the clue itself arises from brilliant piece of deduction and the solution is extraordinarily elegant. The main difference from the screen is that Saville’s instruments are Barney’s extended family rather than Jim’s. Debbie and Kim are mentioned but absent, which feels refreshing rather than an omission.

But that of course brings us back to the two elephants in the novel: Richard and Clare. They don’t appear in the TV series, and there have been scenes where it would have made sense for them to have appeared, had they existed. But Barney and Alice’s behaviour with their previously-secret children does seem consistent and in character with what we have known from the small screen. Personally, I’m convinced, but I’d be interested in the fandom’s views.

Saville has more space than in Crimes of the Season to flex his literary muscles and move beyond someone else’s script, providing us with more of Bergerac’s thought processes. We’re impressed by his approach to policing, knowing when to provide carrots and when to provide sticks and when to do both simultaneously. He does a deal with a journalist, and his explanation to an exasperated Barney is a masterclass in persuasion. And despite one major character being almost cartoonish in their nihilistic approach to life, there’s much humour to be found in these pages, with inventive asides and witty metaphors. The one slightly weird part of this experience is knowing precisely what some of the characters look like, while having to use our imaginations for others. All part of the fun, I suppose, and there’s plenty to be had.

Looking forward to reading the others in this mini-series.

[…] covering attempts to novelise Jim Bergerac’s 1980s TV adventures. In 1988, Penguin brought out the first straight-to-novel adventures. In the same year, BBC Books, which had earlier tried to bring us Bergerac scripts in book form, […]